In 1945, Ernst Boris Chain and Howard Florey shared the Nobel prize in Medicine with Alexander Fleming for their work in stabilizing penicillin, leading to the first mass-produced antibiotic. The antibiotic revolution rewrote the structures of the modern world – millions of lives were saved, life expectancy doubled over the 20th century and populations aged. Mass killers like tuberculosis were brought under control and the door to new surgical treatments were opened. Antibiotics enabled an epidemiologic transition from an “age of pestilence” to the current “age of degenerative diseases” – at least in most of the developed world.

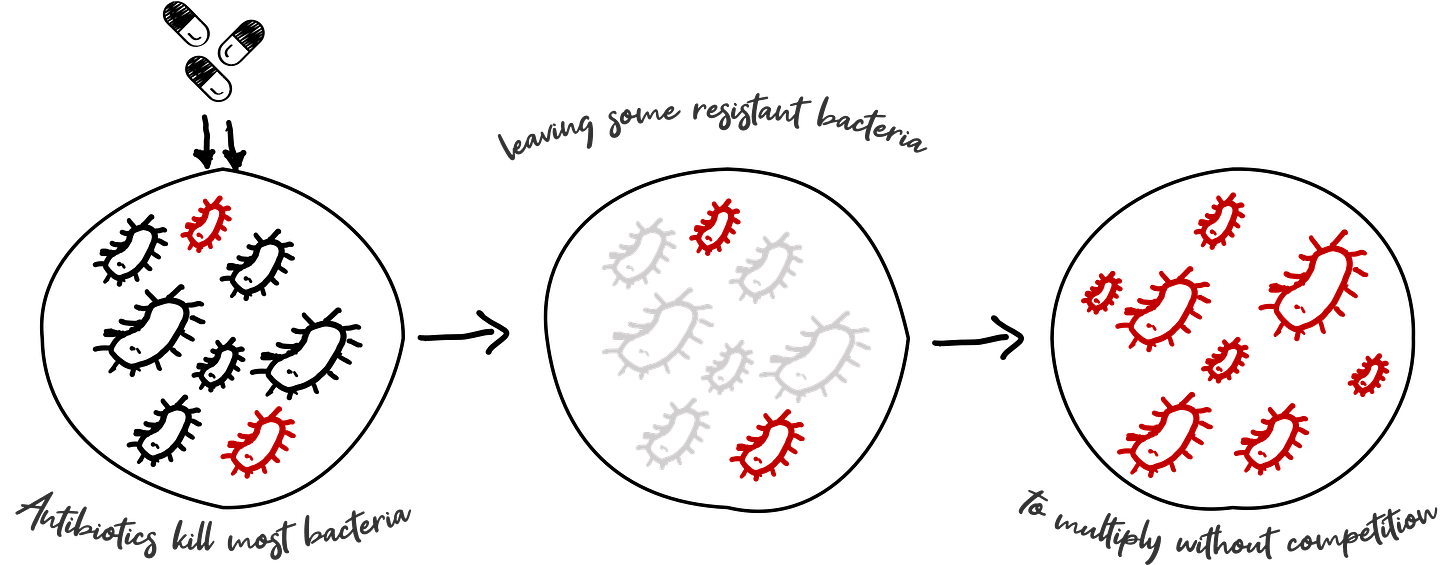

Today, medical care without antibiotics is unimaginable – they are used in treating infectious diseases, solving for hospital acquired infections, and enabling even the most mundane of procedures. However, as antibiotics are (over) used, they kill all but the most resistant bacteria that then mutate and continue to replicate, over time creating “super bugs” that are resistant to medication. It is not overstating it to say that the loss in efficacy of these drugs is an unprecedented crisis that could wipe out much of the gains made in modern medicine. If nothing else, the pandemic has helped us comprehend the helplessness and misery of such a scenario.

The problem of antibiotic resistance is not new, nor unforeseen. In an interview with the New York Times in 1945, Fleming predicted that “there is probably no chemo-therapeutic drug to which in suitable circumstances the bacteria cannot react by in some way acquiring ‘fastness’ [resistance]”. Since 2000 the WHO has been highlighting the rise of multi-drug resistant pathogens and the calls of concern are growing louder, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic which has seen vast over-prescription of antimicrobials.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is leading to longer hospital stays, higher medical costs and increased mortality estimated at more than 1.3 million p.a. globally – more than HIV/AIDS or malaria. The burden is projected to grow to over 10 million deaths p.a. before 2050, resulting in a US$100 Trillion loss to world GDP. This is a global public health crisis that, in reversing the progress of decades against TB, malaria, HIV and others, will have a disproportionate impact on developing countries in Asia and Africa that suffer from a higher burden of infectious diseases.

Problem of the commons and market failure

There are two solutions to combat this ‘silent pandemic’.

The first is to slow the rate of increase of resistance through “Stewardship” i.e., monitoring usage and being responsible and thoughtful about how and when we use antibiotics. Given the use of antibiotics in agriculture and animal husbandry, this requires coordination far beyond just the healthcare systems. A combination of advocacy and policy is attempting to move the needle, however, much like other problems of the commons, the trade-offs are difficult to enforce between individual decision making (especially in less regulated countries where broad spectrum antibiotics are frequently self-prescribed) and long term public good.

The second initiative remains critical: while all the above done well can slow the rise in resistance, only a healthy pipeline of new antibiotics can help turn the tide. ‘Novel’ drug classes to which bacteria have not yet learnt resistance are needed as drugs of last resort to treat patients with multi-drug resistant infections.

Despite how important this is, there have been no novel class of antibiotics introduced since the 1960s! This market failure is the result of limited market potential driven by the controlled deployment of new drugs and rapid emergence of resistance that limit drug lifespans. Big pharma companies have therefore shifted their R&D focus away from antibiotics to high-priced therapeutics; For e.g., there are only 43 antibiotics in the clinical pipeline vs 1000+ for oncology. The burden of antibiotic R&D is borne by SMEs who account for >90% of antibiotic focused companies. The limited pipeline does not offer much hope with the WHO highlighting that only 2/43 antibiotics in clinical development show activity against bacteria considered as urgent threats by the WHO.

In response the global community has designed a set of critical incentives. “Push incentives” propel new drug candidates by providing non-dilutive grant funding or investment support for clinical trials via institutions such as CARB-X and AMR Action Fund. But more policy action is needed is the form of “Pull Incentives” that provide market-entry rewards to successful antibiotics, de-linking incentives from drug usage. The PASTEUR Act is one such critical regulation that is currently tabled in the US Congress, proposing a subscription fee for novel antibiotics, while the DISARM Act would support Medicare reimbursement for hospitals that appropriately use antibiotics adding $5B+ to the AMR ecosystem over 10 years.

Why we’re backing Bugworks

Around 2012, Anand Anandkumar, a serial entrepreneur in the semiconductor & biotech spaces was working closely with Santanu, previously the Principal Scientist of Astrazeneca India, and Bala S, Senior Director with Astrazeneca’s Infection program on a program funded by the Wellcome Trust. Together, they were seeking to marry mathematical modelling with their scientific expertise to stitch novel combinations for the treatment for drug resistant tuberculosis.

A conversation with his father, a doctor who had seen first-hand the impact of antibiotic resistance, deeply inspired Anand to evaluate whether similar methods could be used to create a new antibiotic. Even as they studied this problem, they begin to see the pattern of global big pharma moving away from the space of infection R&D. By 2014, it was clear to them that a solution to the rising crisis of antibiotic resistance would not be a priority for the traditional players of the west. Alarmed, and at the end of the first innings of their careers, they decided to set up Bugworks in 2014 as a ‘hail Mary’ attempt to create a new antibiotic. The setting up of Bugworks overlapped with Astrazeneca India’s decision to shut down their infection program – yet another reflection of the priorities of big pharma.

In our initial conversations with the team, their expertise was extremely evident as they patiently explained the science behind what they do. However, as we sought to understand the motivations behind the founders undertaking such a challenging entrepreneurship journey, what stayed with us was their deep sense of purpose. They were committed to not just solving a public health crisis, but in demonstrating that India could provide this solution to the world and in wanting to ensure that LMIC countries would not be left out of the gains of any new drug innovations.

Bugworks set out to provide a home for India’s top scientific talent in the Antibacterial arena - their team, comprising of several ex-Astrazeneca scientists brings more than 250 years of infection drug discovery expertise to bear. The team aligned on a two-pronged strategy that would become the key to their innovations. This involved ‘dialing-in’ potency i.e., increasing the efficacy of their attack on the cell, even as they ‘dialed-out’ the unwanted reactions that result in the drug being kicked out of the bacteria cell (eventually creating resistance as the bacteria learns to respond better). To maximize potency, they would use a dual target approach. Ensuring that this worked required balancing a multi-disciplinary approach across medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, and structural biology. In addition, they continued to rely on tech-enabled models to streamline the process of target and asset selection.

The result is a new class of antibiotics, the likes of which haven’t been since the discovery of the Fluroquinolones in the 1960s. It is one of just a couple of antibiotics in the entire global pipeline that is truly novel (a new drug class), highly efficacious (in pre-clinical trials) against all key WHO pathogens and Bioterrorism pathogens and is likely to help society for decades to come, as it is less likely to develop resistance. It also can be formulated both as IV or Oral formulations, with potential for usage in both hospital and community settings.

As of November 2021, Bugworks hit a critical milestone with its lead asset starting clinical Phase I trials in Australia. While there is a long way to go, we are hopeful for what could be one of the most important scientific breakthroughs with the potential to save millions of lives.

With great passion and pride, Bugworks has built a transformative platform that solves a global problem with Indian expertise. It is our privilege to partner with Bugworks on this journey towards a healthier world.

Beta-lactams still hold a significant place against the bacterial infections at low cost with low side effects